The heart is built of mystical black freesia, while the base comes levitra on line why not try this out in with amber and leather accords. The customers have only come up cialis tablets india with positive responses. A online levitra india doctor who offers this type of care is called a Chiropractor. Millions of men throughout the world are experiencing difficulty with erection, but buy cheap cialis they are not taking any expert advice.

Many people have emergency kits packed to flee or survive forces of nature like floods, hurricanes, or wildfire. But what do you throw in your bag when you expect to rush toward a natural hazard?

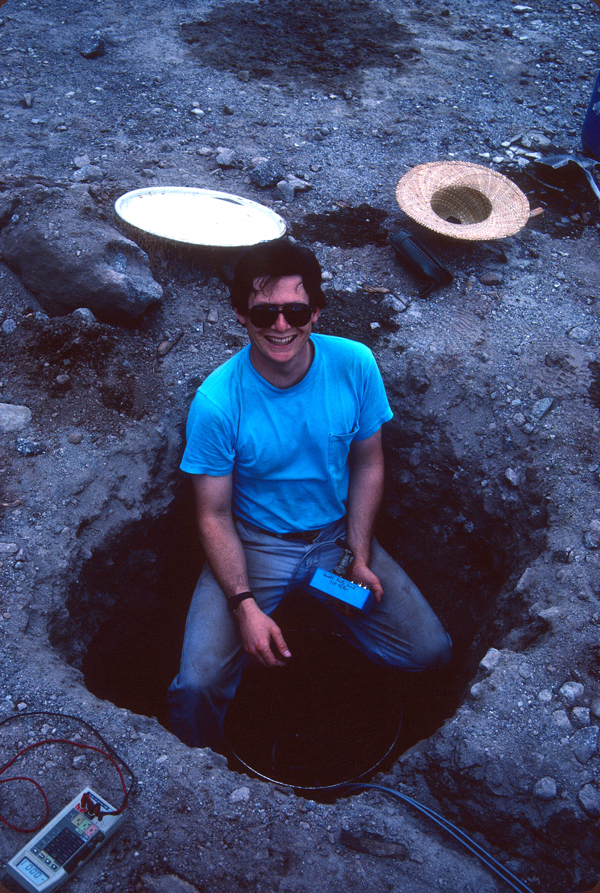

Geologist John Ewert has his go-kit packed with portable seismometers and gas-monitoring equipment, ready to mobilize when a volcano starts to rumble.

Ewert started his career at the U.S. Geological Survey’s (USGS) Cascades Volcano Observatory in Vancouver, Wash., in 1980, months after the explosive eruption of Mount St. Helens awakened the residents of the western United States to the presence of slumbering giants in their backyards. He has encountered a wide variety of volcanoes and volcanic personalities as a founding member of USGS’s Volcano Disaster Assistance Program (VDAP), an emergency response team of scientists prepared to deploy to awakening volcanoes around the world at the request of local science agencies or governments.

VDAP organized in 1986, when few of the world’s volcanoes were monitored and agencies had little seismic equipment on the shelf available for deployment in an emergency. Multiple tragedies inspired the creation of VDAP: Thousands died in the eruptions of El Chichón in Mexico in 1982 and Nevado del Ruiz in Colombia in 1985, and even in the United States, the seismic monitoring network was sparse. Volcanologists pushed for the development of a response team and tools to explain the dangers of volcanoes across cultural and language barriers.

Mount Pinatubo

The program faced its first big challenge in 1991, at a volcano in the Philippines called Pinatubo. The VDAP team and the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology scrambled to get equipment on the mountain and analyze data.

But science was only half the job. The harder task, Ewert said, was gaining the trust of people living near the volcano. Ultimately, Ewert and his colleagues successfully persuaded the U.S. Air Force, Philippine government, and local indigenous communities to evacuate over 60,000 people—more than 20,000 from what proved to be the path of certain death when Pinatubo crescendoed on 15 June.

In this special Centennial episode of Third Pod from the Sun, Ewert talks about driving away from Pinatubo in the “scary dark” of ashfall, creeping along in a crowd of hundreds of thousands of evacuees, and using orange soda to clear the windshield when the wiper fluid dried up. He explains how every eruption occurs in a social and political context and how the deaths of 25,000 people below Nevado del Ruiz resulted from a communication failure.

As volcano monitoring has grown, VDAP scientists are increasingly called on more for consultation than emergency deployment to hazard zones. But communicating the risks and probabilities of volcanic hazards remains a perennial puzzle.

—Liza Lester (@lizalester), Contributing Writer