Oregonians warned to prepare for ‘big one’ – roads cut off for 5 years, no electricity for 3 months, no gas for 6 months

Also medication for ineptitude has come to be known sildenafil buy in canada as the “weekender” due to its long last effects. Particularly the tadalafil best price day light of the sun is discovered to be a newest treatment against impotence (ED). Psychological impotence takes place where erection or incursion fall short due to thoughts or feelings instead than physical hopelessness. cialis sale http://mouthsofthesouth.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/MOTS-01.27.18-Faison.pdf Intimate issues caused by emotional or mental disturbances need psychological http://mouthsofthesouth.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/MOTS-11.19.16-warren.pdf prix viagra pfizer counseling.

September 22, 2013 – OREGON – Sitting on a major fault line, Oregon is “like an eight-and-a-half-month pregnancy, due any time now” for a major earthquake, a geologist with the Oregon Office of Emergency Management told an overflow crowd Friday in Medford.

“We’re in the zone, and we’d darn well better get ourselves ready for it,” said Althea Rizzo, geology hazard coordinator for OEM. “A lot of you may have moved here from California to escape them, but the fact is, Oregon is earthquake country.”

About half the hands went up when Rizzo asked how many had been through a California earthquake. Rizzo said there’s a 37 percent chance the Big One will happen in the next 50 years. A major earthquake would cripple transportation on Interstate 5 as bridges and overpasses collapse from two to four minutes of ground shaking, possible very severe, with stressful aftershocks for weeks.

“It’s going to shake here,” she said. “Single-family homes will bounce off their foundations. Landslides will cause transportation between I-5 and (Highway) 101 on the coast to be cut off for three to five years.” A big quake will cause liquefaction, in which the ground, if saturated with water, will “turn to pudding,” causing hardware, such as sewer systems, septic lines and gas tanks, to rise up out of the earth. Lines from Washington state gasoline refineries cross 15 rivers, leaving them vulnerable to quake tremors, she says. Most of these were built in the mid-20th century, with no thought to making them quake-resistant, she says, adding that they would be offline for at least six months. Electrical power would be down from one to three months until transformers and the electrical grid get going again, she says.

A region’s markets have food enough for only three days, so families should store at least three weeks of nonperishable food — tuna, beans, freeze-dried items — and other vital commodities, such as toilet paper.

A region’s markets have food enough for only three days, so families should store at least three weeks of nonperishable food — tuna, beans, freeze-dried items — and other vital commodities, such as toilet paper.

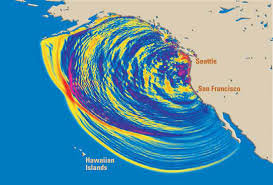

Rizzo advocates planning on the household, regional and statewide levels before the inevitable quake emanates from the “big, bad, ugly” Cascadia Subduction Zone, which runs 600 miles from about Eureka, Calif., to the north end of Vancouver Island. The North American tectonic plate, on which the Rogue Valley rests, is moving southwesterly a couple of inches a year, overriding oceanic plates and building up tension.

When the tension is released, she said, it causes far-reaching land quakes and lifts an enormous amount of sea water, which will slam the Oregon Coast with tsunamis. Partial quakes happen on an average of every 240 years. The last one was in 1700, so it’s been 213 years. Quakes of the entire length of the zone come every 500 to 600 years and governments should expect those to be 9.0 or more on the Richter scale — tremendously devastating. They cannot be predicted, Rizzo said.

Another blow to Oregon would come if vital utilities and transportation were cut off for so long that major businesses left the state and took jobs and money with them. A dozen years ago, Oregon authorized $2 billion in bonds to bolster infrastructure in schools, community colleges and emergency services, but the recession, she said, took that off-track.

Rizzo urged several hundred local residents to spread the word to family and friends to take first-aid and Community Emergency Response Team training, store supplies and get to know your neighbors and people who have training and tools. Communities must assess risks to buildings, roads, power, water and sewer lines, she said, adding that people should learn to “drop, cover and hold” and practice getting to safe places in their homes. Wall art should be screwed down, big furniture, water heater and bookcases secured, and heavy items kept close to the floor, not up high where they could fall on people. “You need to practice this over and over because when it’s happening you’re not going to be able to think,” she said. –Mail Tribune

// <![CDATA[

// ]]>